Marking Lives COVID-19 Exhibition Catalog Now Available: Recording Private and Collective Responses to the Pandemic

By Scott Slovic

As the Omicron surge threatens a dramatic increase in the number of COVID cases and casualties entering the winter months of 2022, artist Elizabeth Awalt has published the catalog for Marking Lives COVID-19: A Community Art Memorial & Exhibition, which was on display at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard September 27 to November 19, 2021. The project was conceived by Elizabeth Awalt in February 2021. She asked participating artists “to make at least 1,000 ‘marks’ on any surface in any medium” as a way to represent lives lost to COVID-19 in the United States.

Giba Gomes

In Awalt’s February 2021 Arithmetic of Compassion blog statement, she notes that the “unsettling statistic” of 270,000 COVID deaths in December 2020 triggered her awareness of the need to “mark” these deaths somehow, despite her feelings of fear, numbness, anger, and helplessness. On her personal website, she observes that as of August 9, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had recorded 614,291 lives lost in the United States. Just below this, she indicates that 193 artists participated in the Marking Lives COVID-19 project, contributing 309 artworks, and displaying 403,460 marks to commemorate the lives lost. Some four months later, the number of lives lost in this country due to the pandemic stands at more than 800,000.

Donna Caselden

The CDC website offers a page under the heading “Wondering what all the data mean?” The focus of this page, in late December 2021, is on how to enjoy “safe and happy holidays” by following six defensive strategies, such as getting a vaccine “as soon as you can,” avoiding crowds, and washing hands. The CDC’s emphasis is on nudging the public toward common sense ways of limiting further spread of the disease. The Marking Lives project seeks a different kind of “meaning” in the COVID data.

Willa Vennema

Physicist and author Alan Lightman, in his Foreword to the catalog (based on an April 2020 essay in The Atlantic), finds that the pandemic has forced many people into isolation, “dislodged” from social routines and jobs. For Lightman, this has been an opportunity to slow down and reflect, “away from the noise and heave of the world.” While many people have resisted such sequestering, artists and writers, suggests Lightman, have used lockdowns and remote work arrangements to gain freedom from “our time-driven lives,” to regain our inner selves.

Susan Lyman

There is no particular correspondence between the 403,460 marks represented in the exhibition and the more than 600,000 COVID deaths that had occurred at the time the artworks were displayed at the Broad Institute, but instead these marks reveal a more flexible practice of “honoring” the diverse “individuals of all ages, races, and genders” who had perished during the pandemic. In her catalog statement, Awalt describes the making and counting of these marks as a process of “honoring,” of acknowledging and respecting the unique individuality of each COVID victim.

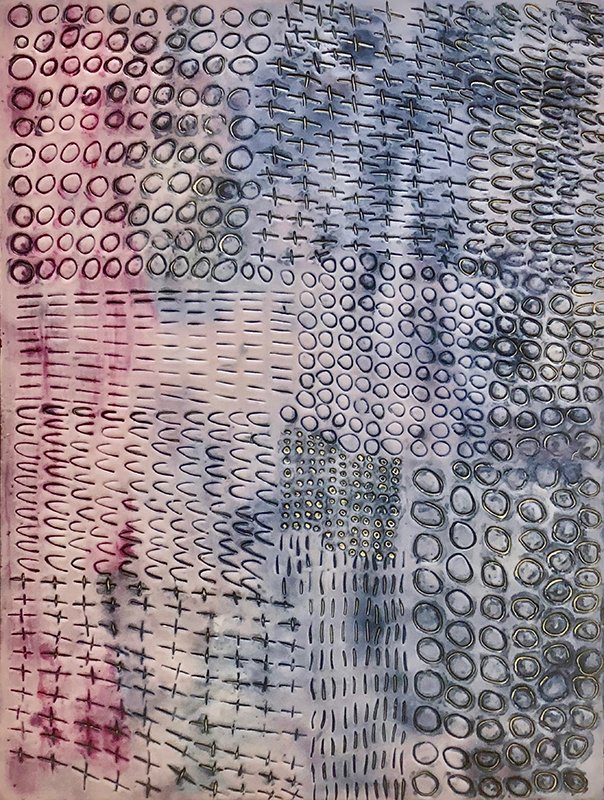

The artworks that appeared in the exhibition and are collected in the catalog are nearly all highly abstract, many of them foregrounding individual brush strokes, or “marks.” There is nothing in the specific works that explicitly represents COVID, no images of the coronavirus or patients in hospital beds. In her catalog essay “When Words Fail: The Emotional Power of Abstraction,” art critic Barbara O’Brien suggests that the works demonstrate the power of “counting,” a quasi-ritualistic process of consciously noting the otherwise unfathomable rise of COVID numbers. She writes: “What each artist did was dutifully count, and the numbers became a staggering metaphor for a pandemic out of control.” Just as the artists performed this ritual of counting, acknowledging with each colorful brush mark that the lives of individual COVID victims matter, visitors to the exhibition (and readers of the catalog) experience this process of registering the “staggering” numbers of cases and deaths by appreciating how gestures of pigment metaphorically represent human beings. The emotional equation between marks and lives is inexact, but patterns of color do inspire a psychological response beyond the vacuum of feeling left by such numbers as 270,000 or 614,291 or 802,969, the latter of which is posted blandly on the CDC site as I type this blog.

The catalog is available for $20 and can be ordered from Elizabeth Awalt’s website.