Risk Perception and Gender: How Bias Shapes Vulnerability

Why do some people perceive risks differently? Our perception of risk is shaped by our identity and social standing. Privileged groups—whether by race, gender, or socioeconomic status—often view risks as manageable, thanks to resources and power. In contrast, marginalized communities face greater vulnerability during crises like climate change or health emergencies.

The study “Gender, race, and perceived risk: the `white male’ effect” by Paul Slovic, Melissa Finucane, et.al., refers to the white male effect: 30% of white males in the U.S. perceive risks, like environmental hazards, as much lower than other groups. This bias reveals a disconnect between those who feel insulated from risk and those who bear the brunt of it.

These disparities reflect deeper societal biases that exclude marginalized voices from key decision-making, amplifying their vulnerability. Gender also plays a significant role, with women often facing higher risks due to societal inequalities. Less participation in decision making and risk management can help explain why women tend to perceive more risk compared to men.

Understanding these dynamics and the gaps between perceived risk and actual risk is critical for creating equitable risk management and inclusive policy.

Let’s unpack these statements with some examples and what can we do about it.

Indian ocean tsunami and hurricane Katrina

Natural disasters often exacerbate deep societal inequalities, with wealth, gender, and caregiving roles shaping survival outcomes. In the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, women in marginalized communities bore the heaviest toll, with up to 70% of fatalities in some areas.

Cultural expectations that prioritize caregiving over self-preservation—such as women delaying evacuation to assist children and the elderly—left them disproportionately vulnerable.

A woman laments the loss of her family in the fishing village of Nagapattinam, India. Photograph by Santosh Cerma/The New York Times/Redux.

Many women, constrained by restrictive clothing and societal norms that discouraged swimming, had limited options for escaping danger. These biases highlighted the urgent need for gender-sensitive disaster planning.

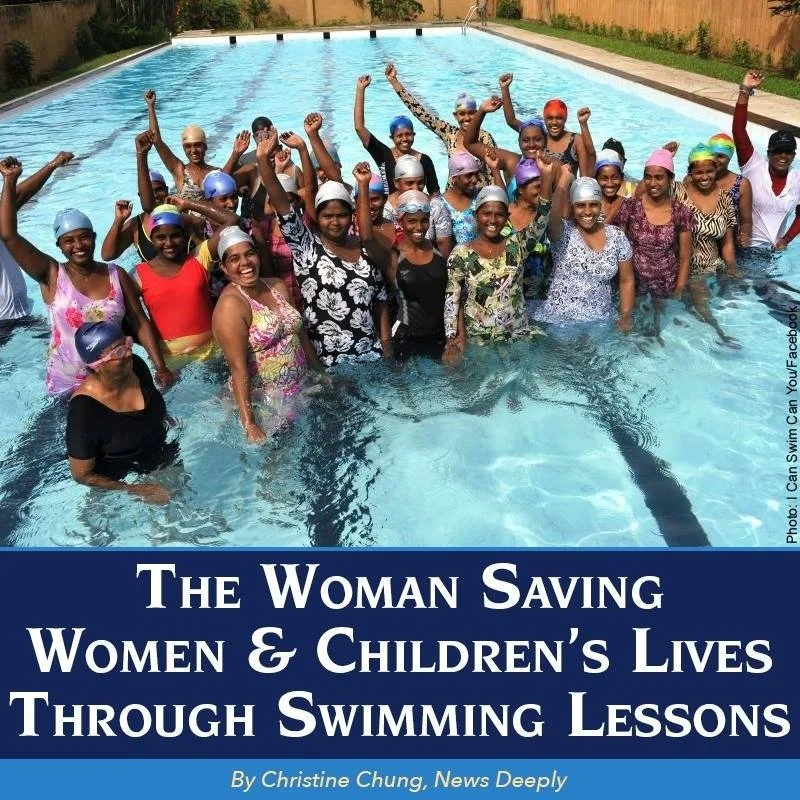

Yet, over the years community-led initiatives provided hope, exemplifying the power of collective efficacy. In 2006, Women without Borders taught over 80 women in Chennai to swim, defying cultural resistance and restrictive dress codes. Such grassroots efforts not only saved lives but also challenged the structures that perpetuate vulnerability. Empowering women is essential for equitable disaster resilience.

Similarly, during Hurricane Katrina, women faced compounded challenges. Often responsible for the care of children and elderly family members, women delayed evacuation, increasing their exposure to harm.

Photo: IWPR. June 2010. New Orleans.

Post-disaster, systemic biases continued to hinder recovery efforts. Aid systems prioritized "heads of households"—typically men—leaving women, who were often the primary caregivers and breadwinners, without the support they needed. In New Orleans, this inequity was glaring, as many women struggled to access vital relief.

Organizations like Women of the Storm, founded by women affected by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. By uniting a diverse group around a shared purpose, they advocate for the Gulf Coast through Congress, the media, and public opinion, demonstrating how coordinated action can bring about lasting change.

And what about the Queer community?

Disasters disproportionately also affect LGBTQ+ individuals, especially queer women, transgender people, and queer people of color, who often face unique vulnerabilities due to systemic discrimination.

After Hurricane Katrina, queer women and trans individuals experienced compounded challenges. Many lived in hard-hit areas like mid-city New Orleans, far from the traditionally gay male neighborhoods spared by the flooding. Post-disaster, legal systems built around heteronormative assumptions left LGBTQ+ families without support.

Sharli’e Dominique, a transgender woman, was jailed after using a women’s restroom at a shelter post-Katrina, despite prior permission. Her situation improved only when an HIV clinic director offered her shelter, highlighting the compounded discrimination LGBTQ+ individuals face during disasters.

Biases in risk perception have life-and-death consequences. Tackling these challenges requires dismantling harmful norms and actively involving marginalized groups, including women and the LGBTQ+ community, in decision-making roles.

Supporting organizations such as OutRight Action International, which advocates for LGBTQ+ inclusion in crisis planning, can help dismantle systemic inequities and build equitable, resilient communities.

Men and Women behind the wheel: from driving to decision-making roles

Biases in risk perception extend beyond disasters, shaping outcomes in everyday contexts such as road safety. Gendered disparities in vulnerability reflect the same structural inequalities that exclude marginalized voices from decision-making roles.

According to the Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI), many more men than women die each year in motor vehicle crashes. Men typically drive more miles than women and are more likely to engage in risky driving practices, including not using seat belts, driving while impaired by alcohol and speeding. Crashes involving male drivers often are more severe than those involving female drivers (Li et al., 1998). However, females are more likely than males to be killed or injured in crashes of similar severity (Kahane et al., 2013)

A 2012 study reported inTime Magazine further illustrates these behavioral differences, showing that women tend to adopt more methodical parking techniques, such as reversing into spaces with greater precision. In contrast, men often prioritize speed over accuracy, sometimes leading to less optimal parking outcomes. Could this reflect broader patterns of risk-taking behaviors?

Cigarettes and risk perception across genders

The "Torches of Freedom" campaign by Edward Bernays demonstrated how societal norms could be manipulated to shape risk perceptions. By framing cigarettes as symbols of women’s empowerment, Bernays tapped into gender disparities to normalize smoking. This male-driven narrative exploited the gap between perceived liberation and actual health risks.

Today, data also reveals that women are twice as likely as men to develop lung cancer when exposed to cigarette smoke (American Lung Association, 2024). Gender-specific risks. Despite targeted marketing claiming “safer” alternatives, women smokers continue to face heightened vulnerabilities.

Do perceptions of risk align with actual vulnerability? And how do societal structures amplify or mitigate these disparities? Addressing these questions is critical to understanding and bridging the gender gap in risk perception.

This video describes how gender structural biases shape vulnerability.

Supporting organizations like Equality Now, OutRight Action International, and CIHR's Gender and Health Promotion Studies is a step forward in advocating for inclusive policies. By fostering collective action and promoting diverse leadership, we can bridge the gap between perception and reality, ensuring resilience and equity for all communities.