Why Does Bad News Stick While Good News Fades?

By Emiliano Rodríguez Nuesch and María Morena Vicente

Every day, we are bombarded with alarming headlines—crime, disasters, corruption. But when good news happens, it rarely commands the same attention…

Everyone remembers 9/11 in 2001, for example—a day of tragedy that shaped global events. But did you know that in that very same year, groundbreaking advancements were also taking place?

The first draft of the Human Genome was published, unlocking new possibilities in medicine. The United Nations adopted the Millennium Development Goals, setting a global framework to fight poverty and improve lives. Polio vaccination efforts made significant strides toward eradicating the disease. Even when terrible things happen, progress continues.

Why do we focus so much on bad news? And how does this shape our perception of the world?

Let’s dive into the psychological principles behind our perceptions of the good and the bad news.

Psychologists have found that bad experiences have a greater psychological impact than good ones across multiple domains, from relationships to decision-making. As Baumeister et al. (Bad Is Stronger Than Good, 2001) explains, "bad emotions, bad parents, and bad feedback have more impact than good ones, and bad information is processed more thoroughly than good." This may help explain why negative news dominates headlines and why our brains hold onto bad experiences longer than positive ones.

The negativity bias is our tendency to notice, remember, and react more strongly to negative information than positive information. This bias evolved as a survival mechanism—our ancestors who were more attuned to threats, such as predators or dangerous environments, had a better chance of surviving.

As cognitive scientist Lisa Feldman Barrett explains, “Memory, like attention itself, is a completely biased system that evolved to privilege survival. That’s why scary or stressful experiences are more prominent.”

Credit: The Decision Lab

But in modern society, this bias explains why we are drawn to bad news, and why fear-based messages often feel more persuasive than positive ones. While negativity bias helps us respond quickly to potential dangers, it can also lead to heightened anxiety and an overestimation of certain risks.

The negativity bias is closely linked to loss aversion. As Daniel Kahneman explains in Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), 'the brains of humans and other animals contain a mechanism designed to give priority to bad news.' This means we are naturally more affected by potential negative outcomes. In his experiments, Kahneman and his research partner Amos Tversky found that people tend to feel the pain of a loss much more strongly than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. As a result, when making judgments and decisions, we place greater weight on negative aspects of events or stimuli.

These paradoxes create a challenge for media, advocacy groups, and humanitarian efforts. They rely on negativity bias to capture attention, yet struggle against psychic numbing when trying to sustain engagement. For instance, a single starving child can inspire donations, but statistics about famine often fail to elicit the same response. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for effective disaster risk communication and storytelling that drives meaningful action.

The negativity bias is also connected to the availability bias—we judge the likelihood of an event based on how easily we can recall examples. Because bad news is more frequently reported, we assume bad things happen more often than they actually do.

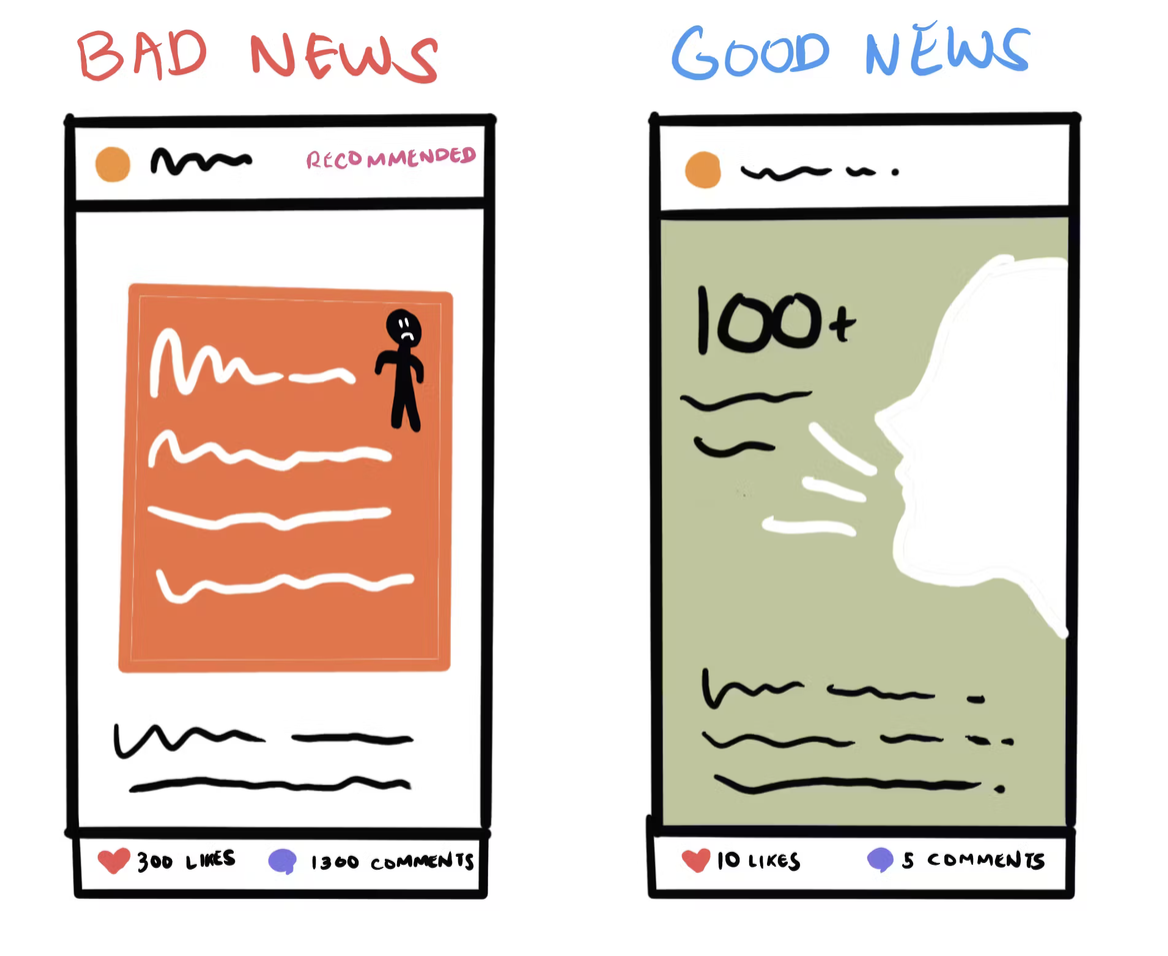

News outlets know that bad news grabs attention. Studies show that headlines with negative words like crisis, fear, and danger get more clicks. TV news stations use fear formulas—repeating shocking stories and emphasizing personal risk—to keep audiences engaged.

AFP/Getty Images

Can Good News Break Through?

It’s not all bad. Positive stories can resonate when told effectively. Take The Good News Movement, a social media page dedicated to uplifting stories, or actor John Krasinski’s “Some Good News” series during the pandemic, which gained millions of viewers. People crave balance, and when given the choice, many engage with hopeful stories.

Here’s another example: David Lynch’s Weather Report during 2020 “I’m wearing sunglasses because I’m seeing the future and its looking very bright”.

Similarly, journalist Bryan Walsh launched a newsletter that fights back against “doom scrolling” and it’s dedicated to highlighting progress, optimism, and the remarkable things happening in the world—without ignoring the challenges. Walsh argues that the media, the audience and the brain have a bad news bias.

Is there a good side to negative news?

In the end, we may never fully get rid of our natural tendency to focus on the negative. Since praise, affirmations, and quick fixes don’t override this bias, perhaps the best approach is to recognize its benefits—especially its ability to help us see reality clearly, adapt, and survive. Some researchers call this ‘depressive realism,’ the idea that those who feel down often have a more accurate view of the world, particularly when it comes to understanding their own influence and limitations. Problems like international disputes won’t be resolved with positive thinking alone—realism is just as important.

Credit: The Decision Lab

When it comes to solving global conflicts, we can’t ignore the negativity bias. In the end, we need both perspectives to help us share resources, negotiate peace, and work together.

Simple Steps to Overcome Negativity Bias

Finding balance is key. We won’t stop consuming bad news, nor should we—staying informed is crucial. But we can counterbalance negativity by:

Train Your Brain to Notice the Good – Keep a gratitude journal or share daily wins with a friend. Small shifts can rewire how we perceive the world. Amplify good stories on social media to help them spread.

Reframe the Narrative – Instead of seeing only problems, look for solutions. Follow sources that highlight progress in global issues, like environmental recovery or disease eradication. Engage with solution-based journalism, which focuses on how problems are being solved rather than just the crisis itself.

Diversify Your Media Diet – For every crisis headline, balance it with a hopeful story. Consider subscribing to newsletters like Reasons to be Cheerful. Seek out positive news sources like The Good News Network or Future Crunch.

Limit Exposure to Sensationalism – Recognize when headlines are designed to trigger fear rather than inform. Choose in-depth reporting over fear-driven, clickbait news. Be mindful of your consumption, limiting excessive mindless scrolling.

Actively Seek Context – When bad news dominates, look for historical trends. Many crises today—like poverty and disease—are improving long-term despite short-term setbacks.

Bad news has a purpose—it alerts us to dangers and injustices. But for a clearer view of reality, we must also recognize the medical breakthroughs saving lives, and the acts of resilience that rebuild communities after disaster.