There was a genocide here: my visit to the S21 Museum in Cambodia

By Emiliano Rodriguez Nuesch

The S21 Genocide Museum in Cambodia, officially known as Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, is famous as a poignant memorial to the atrocities committed during the Khmer Rouge regime led by Pol Pot from 1975 to 1979.

I had the opportunity to visit it last April in Phnom Penh. Here’s what I learned and how I felt.

A genocide in a former school

The museum attracts scholars, researchers, and tourists from around the world, making it an important educational tool for international audiences to learn about genocide and human rights.

As I entered, I was immediately reminded of the ESMA Museum back in Argentina, my home country. Both sites denounce state terrorism and preserve the memory of human rights violations.

Originally a high school, the building was converted into Security Prison 21 (S-21) and became Cambodia’s largest center of detention and torture.

S-21 remains one of the few sites that illustrate the brutal policies and actions of the Khmer Rouge regime, under which an estimated 1.7 to 2 million people died due to starvation, forced labor, and execution. It is hard to grasp the scale of the atrocity: nearly 25% of Cambodia’s population at that time was killed in detention centers like this one.

The face of the victims

The museum holds extensive evidence of the genocide, including thousands of photographs that the Khmer Rouge took as part of their documentation process.

These photographs of prisoners are powerful and haunting reminders of the regime’s brutality. By photographing prisoners upon their arrival, the regime instilled fear and asserted control. The act of taking a photograph was a part of the process of dehumanization and submission.

Today, each photograph is a reminder of the individual lives that were brutally cut short. Each image represents a person who suffered tremendously under the Khmer Rouge regime. You can feel that when looking at each one of them.

Each detainee was assigned a number in the S21 prison. Replacing people’s names with numbers is a tactic commonly used to dehumanize people and make it easier to abuse them. More than 18,000 people were detained in this center, out of which only seven survived.

The museum is a place where visitors can pay respects to the victims. The personal stories, belongings, and torture instruments displayed help in understanding the immense human suffering that occurred.

Firsthand testimonials are crucial for breaking psychological barriers because they create a personal connection and evoke strong emotions by fostering a sense of empathy. They give survivors the chance to speak their truth, empower them and validate their experiences.

Vann Nath is one of the very few survivors in Pol Pot’s deadly prison. In an interview for The Guardian, he expressed: “We were so hungry we would eat insects that dropped from the ceiling,'" the 63-year-old said. “We would quickly grab and eat them so we could avoid being seen by the guards. We ate our meals next to dead bodies, and we didn’t care because we were like animals.”

The museum also portrays shocking audio stories, not only from survivors. One recording is from one of the executioners who declared he had killed more than 10,000 people by beating with a club, without using a gun. He mentioned that he now feels sad for those victims. I was shocked.

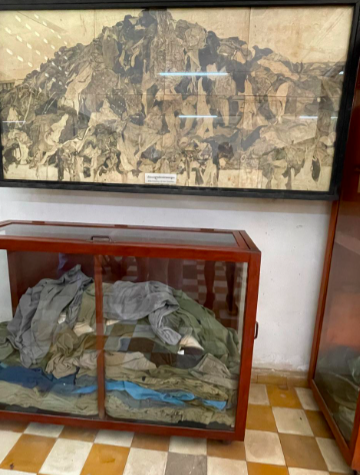

A rigorous documentation process was undertaken to classify and preserve evidence of the atrocities and suffering, including children’s clothes and marks on the walls.

The textile documentation is particularly moving, including quotes and testimonies from those involved in the classification and preservation process. It was evident that they were both emotionally affected by their work and proud to participate in preserving evidence of the genocide.

The experience of visiting the museum was profoundly disturbing.

However, learning about the trials and the accountability process gave me a sense of closure. It was reassuring to see that those responsible were brought to justice and condemned, mirroring the fate of the dictators in Argentina.

Article and photos: Emiliano Rodriguez Nuesch.